Introduction

Artificial Intelligence technologies are computationally intensive. The recent exponential development and deployment of these technologies has increased the demand for digital services, which has a direct effect on the energy consumption of data centres, the physical infrastructure that supports the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector and today’s digital economy. Globally, data centres account for around 1.5% of final electricity demand, with the United States (US) being the largest consumer in 2024 (45%), followed by China (25%) and Europe (15%). This figure is expected to double by 2030, driven by AI adoption and deployment (International Energy Agency, 2025).

The increasing energy consumption of data centres raises environmental concerns, as their energy demands are supplied by the local electricity grid, which in many regions still relies heavily on fossil fuels. In the European Union, these issues are front and centre, as policymakers balance ambitious digital expansion with the region’s strong climate commitments. The European Green Deal sets a target to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 (from 1990 levels), with the broader goal of climate neutrality by 2050. At the same time, the EU is making major investments—over €200 billion—in artificial intelligence, aiming to position Europe as a global leader in the field.

While there is substantial research on the global energy use of data centres, there is still a need for consistent, comparable estimates across EU countries. This thesis addresses that gap by applying a bottom-up, data-driven model to estimate both energy consumption and carbon emissions of commercial data centres across the EU, using geospatial analysis and electricity grid data.

In this thesis, I developed a data science pipeline that extracts and cleans information from public data centre listings, enriches it with operational benchmarks, and links each site to the carbon intensity of its local power supply. The results provide a detailed map of the environmental footprint of data centres in Europe, supporting evidence-based policy discussions on sustainable digital infrastructure.

Methodology

For estimating how much energy do commercial data centres use across the European Union, and how much CO₂ do they emit, I applied a data science pipeline, starting by scraping and cleaning information of 1,600 active data centres from an industry website (Data Center Map) and collected details like their addresses, descriptions, building size, and power capacity. I then validated and improved the location data using geocoding tools, so every facility could be accurately mapped across the EU.

Because industry data is often incomplete, especially when it comes to IT floor space (whitespace), I developed an imputation strategy based on facility classification. Not all data centres are the same. Some are massive “hyperscale” facilities run by companies like Google or Amazon; others are shared buildings (colocation) or private company facilities (enterprise). I first sorted facilities using rule-based keywords and known operator names, then trained a machine learning model to check and refine these classifications. This let me confidently assign each centre to a type, and estimate missing values using typical characteristics for each group.

To estimate energy use, I applied an area-based formula that takes into account IT floor space, how densely the equipment is packed (using IT density benchmarks from Jerléus et al.), and how efficient the centre’s infrastructure is, using a PUE measurement that accounts for the total energy used by the facility compared to the energy delivered just to the IT equipment. I modeled three scenarios—“best case,” “mid-case,” and “worst case”—to capture the range of possible variations on efficiency and energy consumption.

Finally, I combined these results with grid carbon intensity data for 2024 from Electricity Maps, matching each centre’s location to local power emissions factors. By multiplying energy use by carbon intensity, I estimated annual CO₂ emissions for every data centre in the dataset. This bottom-up approach provides a detailed and policy-relevant picture of the climate impact of digital infrastructure in the region.

Results

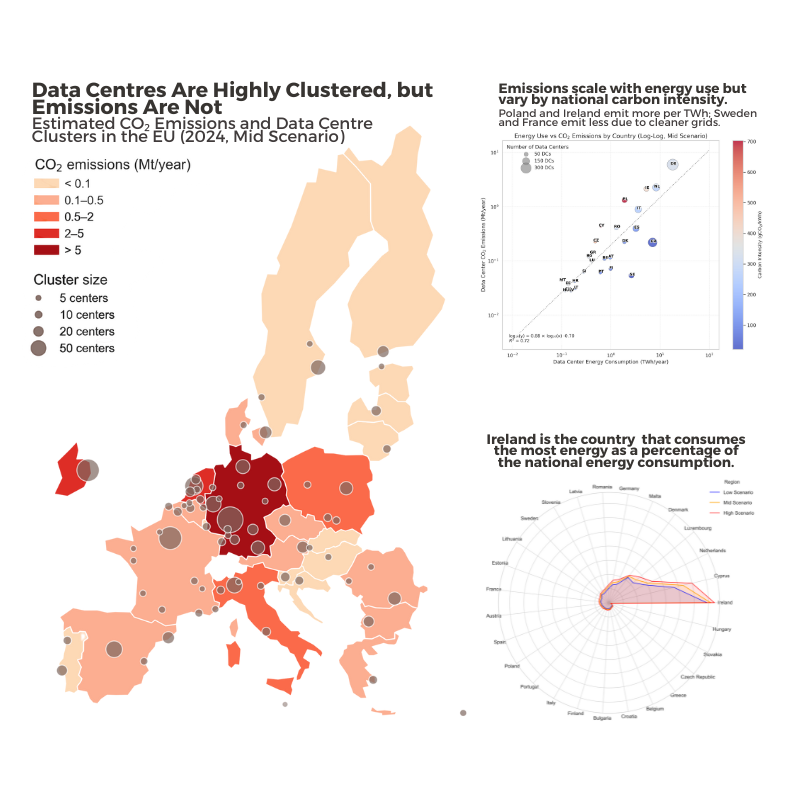

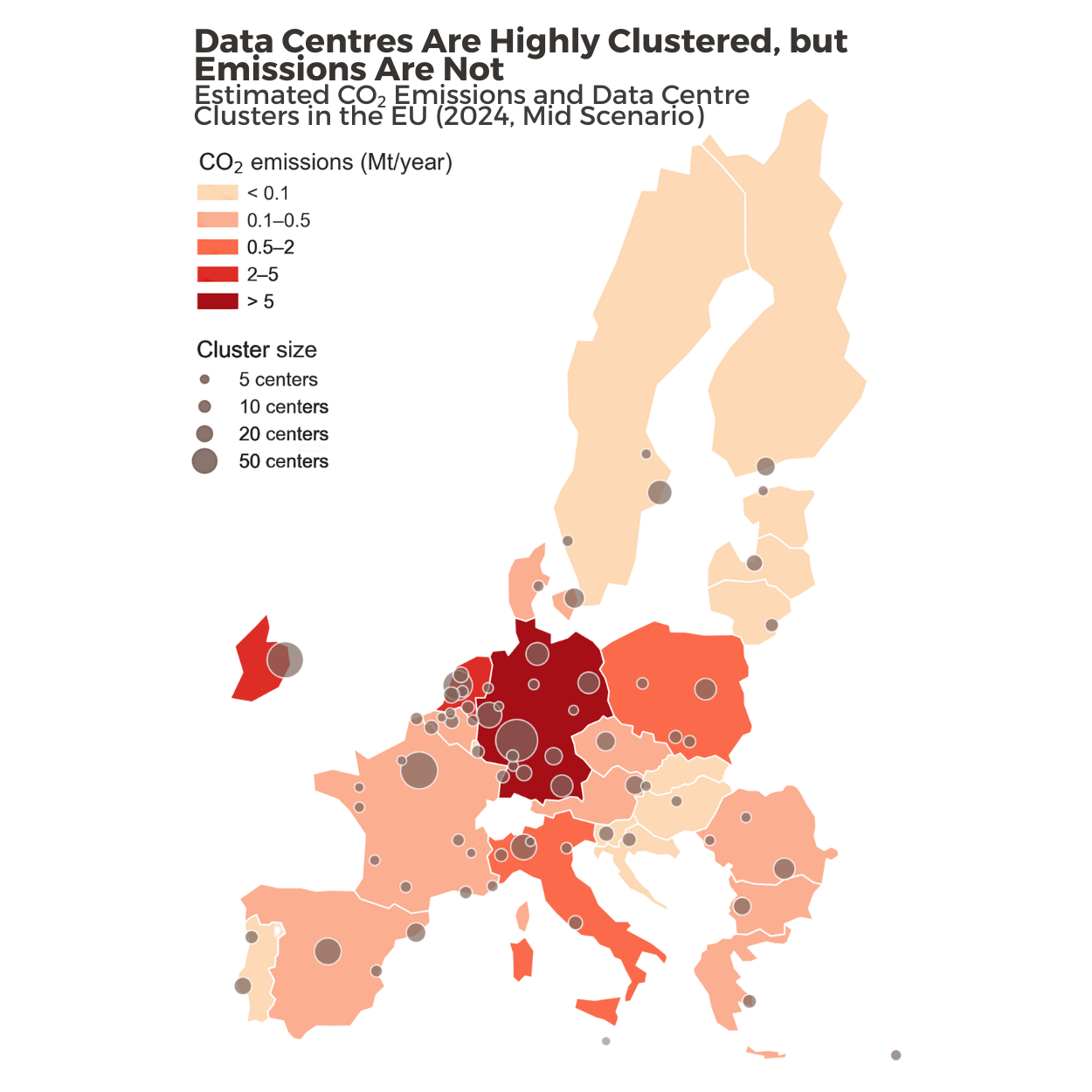

After cleaning and mapping the dataset, I identified 1,600 active data centres across the EU-27. The results show that data centres in the EU are highly concentrated in a few Western European countries—especially Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Ireland—and tend to cluster in major urban hubs like Frankfurt, Paris, Dublin, and Amsterdam. This reflects both the networked nature of the industry (which benefits from existing digital infrastructure and connectivity) and the market incentives to locate near major population centres.

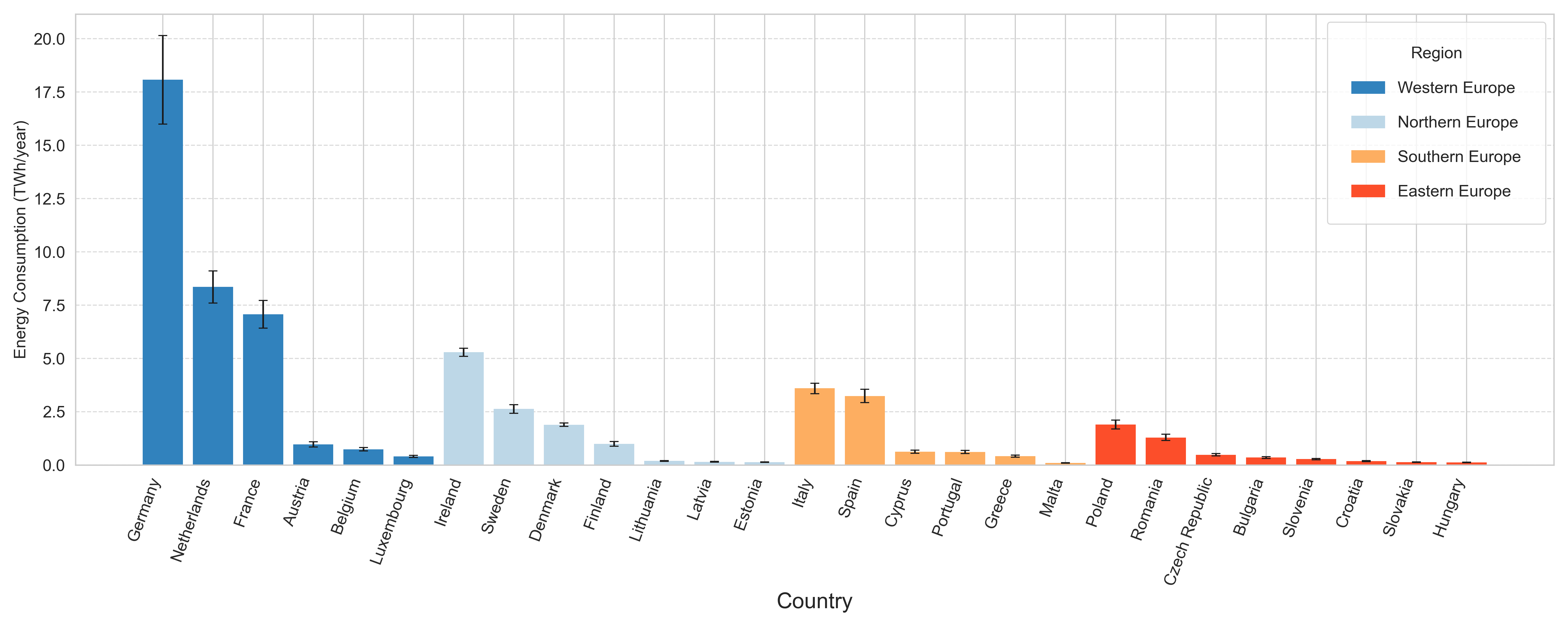

In terms of electricity use, I estimated that EU data centres consume between 54.5 and 65.8 terawatt-hours (TWh) annually, depending on operational efficiency, with a central estimate of 60.1 TWh per year. Western Europe accounts for nearly two-thirds of this total. Germany leads with the highest national data centre electricity demand (18 TWh), followed by the Netherlands, France, and Ireland. In Ireland, data centres are responsible for a substantial share of total electricity use, where they account for about 18% of national consumption, compared to under 4% in Germany.

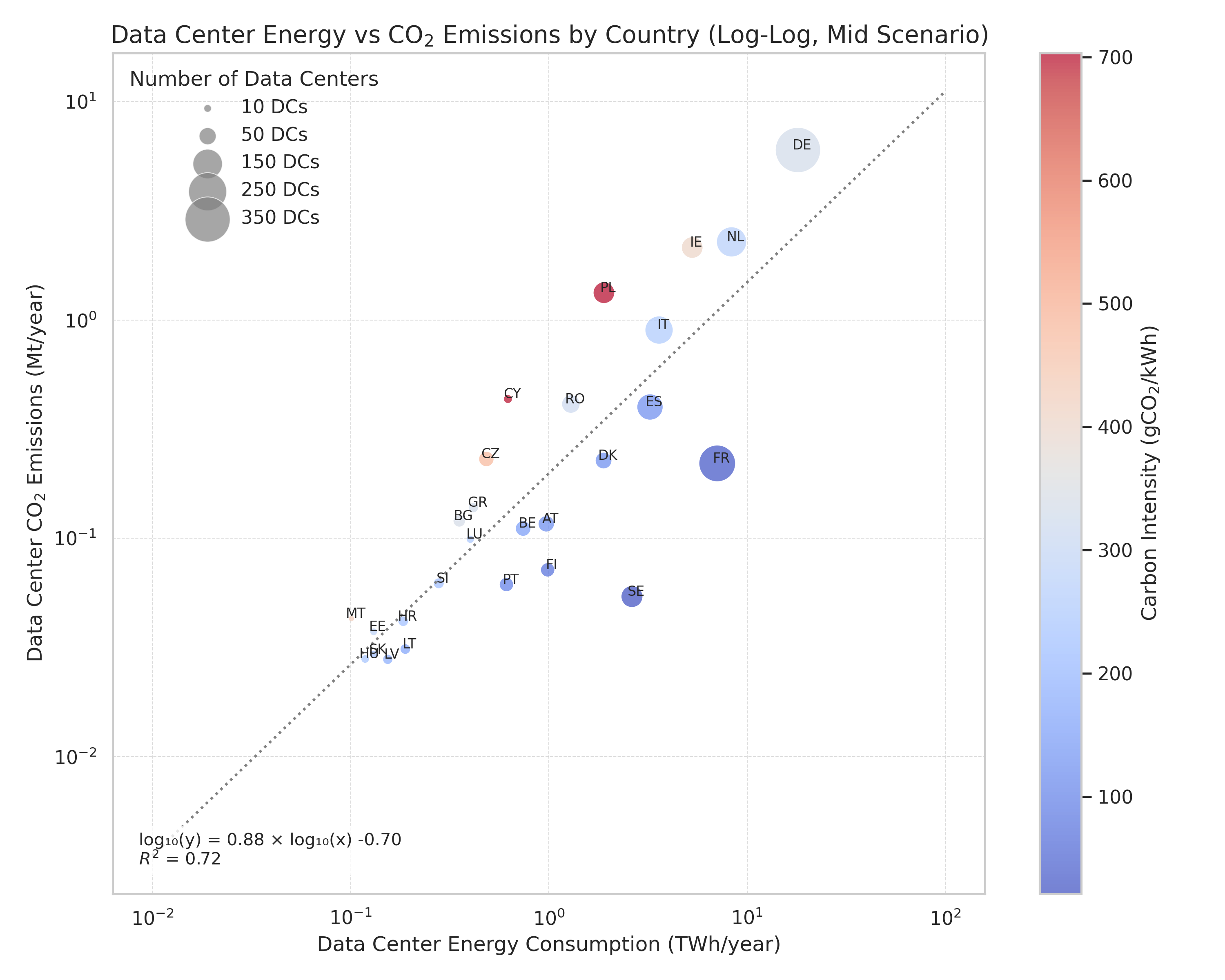

When translating energy use into carbon emissions, I found that EU data centres emit between 14.2 and 17.2 megatons (Mt) of CO₂ each year, with a mid-scenario of 15.7 Mt. Germany again leads in total emissions, but the climate impact of data centres also depends on the carbon intensity of the national grid. Countries like Poland and Ireland, which rely more on fossil fuels for electricity, have higher emissions per unit of energy. In contrast, Sweden and France, with cleaner energy mixes, show much lower emissions even when hosting large numbers of data centres.

This analysis reveals that data centres are highly concentrated in specific regions, represent a significant and growing share of electricity demand, and have a climate impact that varies widely depending on both their size and the local power grid. These findings can help to understand where digital infrastructure is placing the greatest pressure on energy systems and climate goals, and where targeted action might be most needed.

Policy Implications and Limitations

My estimates suggest that data centres in the EU consume between 54.5 and 65.8 TWh of electricity per year—roughly 2–2.6% of the region’s total electricity demand. These figures align well with other recent studies. However, the impact varies widely across countries. For example, data centres in Ireland make up nearly 18% of national electricity consumption, while the share is below 4% in Germany and France. This highlights how digital infrastructure can put a disproportionate strain on smaller or less industrialized grids.

Annual CO₂ emissions from EU data centres are estimated at 14 to 17 megatons—several times lower than U.S. levels. The difference is not simply due to fewer facilities in Europe, but reflects the EU’s cleaner electricity grid. This points to an important policy lesson: the carbon impact of data centres is tied as much to energy sources as to energy use. Decarbonising the grid is central to managing the sector’s climate footprint.

There are also clear differences within the EU. Countries like Poland, which still rely more heavily on fossil fuels, see higher emissions from data centres even with fewer facilities. Meanwhile, countries like France and Sweden benefit from lower emissions thanks to cleaner power.

As AI adoption grows, there is a real risk that data centre electricity demand will increase faster than improvements in efficiency or the rollout of new renewable energy. In some regions, grid capacity is already struggling to keep pace—seen in connection delays in places like the Netherlands and Germany. This creates bottlenecks that could slow digital expansion or raise emissions.

Policy should focus on encouraging data centre growth in regions with abundant renewables and available grid capacity. Continued investment in grid infrastructure, improved cooling technologies, and robust energy data reporting will be critical to managing these pressures.

There are, however, some key limitations in this analysis. The study is based on industry listings, which can be incomplete or uneven—especially for countries with less transparency or smaller digital markets. Many facilities do not publicly report energy use or capacity, making it necessary to estimate missing values. The upcoming EU Energy Efficiency Directive, which will require large data centres to report energy and efficiency data from 2024, should help fill these gaps and improve future assessments.

Conclusion

These findings show that the environmental impact of data centres depends not only on how much energy they use, but also on how that energy is produced. As the EU works to become a leader in AI and digital technology, aligning data centre expansion with clean energy and smart infrastructure planning is critical. Stronger reporting requirements, strategic siting near renewables, and continued grid investment will be essential to ensure the digital sector grows in line with Europe’s climate commitments.

The complete text and code I used for this project can be found here.